Beating a Dead Horse

Cliches! Oh how we writers hate them and are horrified when we find ourselves using them. We do everything we can to banish them from our heads. But this may be the very reason they have such power over us–the forbidden is always that which arises first, I’ve noticed. So I say write them down. I’m not saying use them, but you have to get them out before you can find the fresh take.

When the words are flowing for me, I put down the dreaded cliche (or equally dreaded almost-right word) and make it red. Then, the next day, I just riff on those words or cliches. I write down everything I think of in the riffage session because what starts to happen is the words go deeper. They start to line up and suggest other words and ideas. And when I have a whole string–I’ve had as many as thirty words in a row–I start to look at the chain I’ve made.

Red words!

Red words!

Is there some deeper idea I’m actually getting at? Is there some other feeling I’ve masked up to now by the “wrong” cliche or word choice? Is my character screaming and holding a huge sign that says “I AM ACTUALLY SAYING THIS!” What is the story trying to tell me?

This is why those long word/idea strings are so important. If you just run through them in your head, you’ve lost your whole train of thought. And that train is leading you somewhere. You need to be able to see all the cars because the thing you’re looking for is the engine.

The engine is what’s really at the heart of your story. It’s the emotion that’s fueling the story in the first place. You might think it’s ridiculous not to know what that is–if you’re writing the story, you must know what it’s about, right?–but, just like in real life, there is what’s happening on the surface, and there’s what’s really going on underneath, and it’s not always easy to find, or face, what that is.

Sometimes you realize the engine is actually parts of two or three of the ideas you’ve recorded. Sometimes in the list of wrong words, looking up more synonyms for that one that showed up three times reveals the engine. And sometimes the engine can only show up because you’ve gotten those thirty other words out of the way.

The more you struggle with finding the right word, the more familiar you get with that itchy feeling that arises when it’s not the right word. That itchy feeling is a signal–you’re on the wrong track. You’re not yet clear about what’s really going on in your story.

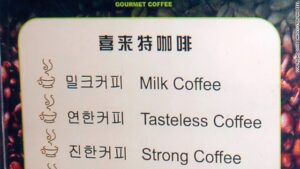

Three very different words. They lead to three very different stories.

Because ultimately, you’re not really struggling to find the right word. You’re struggling to find out which deep, quiet voice inside you is fighting to get itself on the page. And all those red words are the barriers we put between us and what shows up when we turn over the rocks in our souls. No wonder I’ve got strings of thirty words! Give me words, dear god, so I don’t have to look at the creepy crawly things that live in the dark of my mind.

Sometimes the engine takes its time showing up. I’ve had stories with several word/idea strings in them up to the final edit. For those tough ones, I know there’s something not clear in my exploration of what that story is really about. (Dialogue in your final scene is another indicator of trouble–if you can’t decide what a character should say, something’s not clear!) If everything was clear and flowing the way it should be, I would know what word was needed.

That’s when I start again at the beginning of the story. We are building themes, symbols, and meaning from the first word on the page—we are expressing a deep emotional truth—and in a well-strung-together story each word and idea leads to the next and follows from what came before. If I can find those breaks in the links, understand what they’re really calling for, and fix them, often by the time I get to that red train, it’s obvious what word or idea needs to be there. But I can’t be afraid of diving into my own swirling inner world.

“Wrong word/idea,” then, is not just a stylistic choice. It’s also a red flag for something you haven’t yet understood about what you’re really trying to do. And cliches, then, are even worse–they’re the short-cuts writers use to avoid a truly examined life.

But what of the power of cliches? There’s no denying their power to evoke. And a brilliant writer can tap that power and use it to make a ho-hum image indelibly imprinted on the reader’s mind; but only if he or she can bring that inner world to bear upon it.

Cliches are the only way to tap into your reader’s mind and know what you’re going to get. And that’s where we can slam the engine they think they’re driving into the rock wall of their own expectations. Take this one from Margaret Atwood:

“You fit into me

like a hook into an eye

a fish hook

an open eye.”

Aw, that’s so sweet! says her reader after the first two lines. As writers, we know exactly what that reader is thinking: they’re lovers, they’re meant for one another, the reader can safely assume a hundred thousand things about how they function together as a couple.

And then the mental image formed by the last two lines.

Smash!

From “warm fuzzy relationship” to horror story in six words and the reader’s imagination. The second image is as powerful as it is because of two things: the power of the feelings evoked by the initial cliche, and the power of Atwood’s ability to nail those feelings most of us shy away from.

Try and get that image out of your head. It’s been in mine for twenty years.